Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

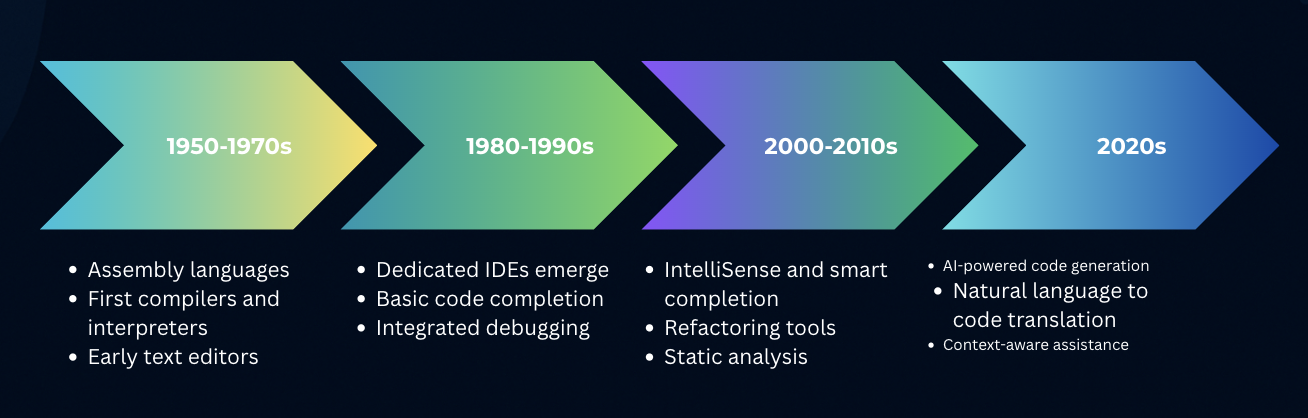

From hand-assembling instructions to AI in your editor, the developer toolchain keeps compressing the distance from idea to working software:

Coding assistants like GitHub Copilot, Cursor, Cluade Code etc. have revolutionised software development. But how do these AI-powered tools actually generate code suggestions and understand programming contexts? Let’s explore mode detail and processes that make these tools possible.

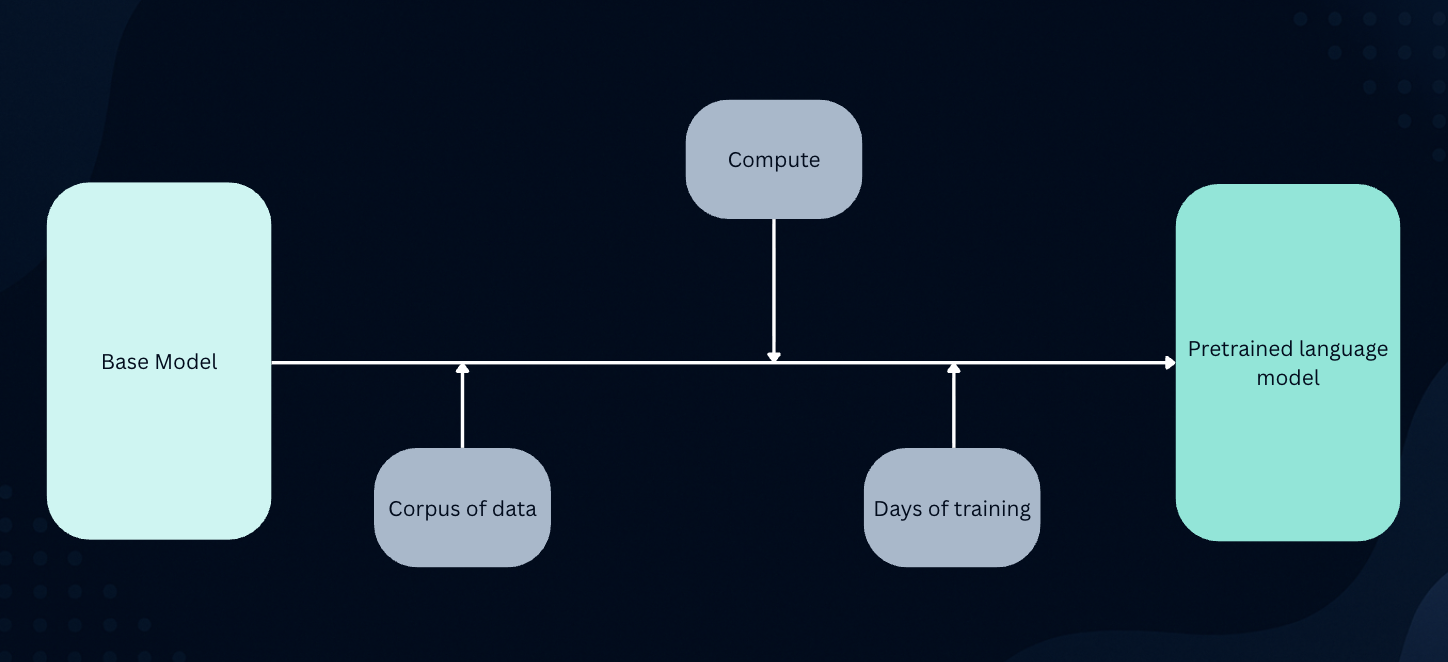

At the heart of almost every coding assistant is something called a Large Language Model (LLM). Think of an LLM as a super-smart, super-trained brain that has read an unimaginable amount of text. In the case of coding assistants, these LLMs have been fed vast quantities of publicly available code from repositories like GitHub, along with countless articles, documentation, and even natural language text.

At its core, a Large Language Model is a type of artificial intelligence – specifically, a massive deep learning model trained on large amounts of data.

Imagine this: The LLM has digested trillions of lines of code in various programming languages (Python, JavaScript, Java, C++, etc.). It doesn’t just memorize them; it learns the patterns, structures, and relationships within that code. It understands how variables are declared, how functions are written, common algorithms, and even how different parts of a program usually fit together.

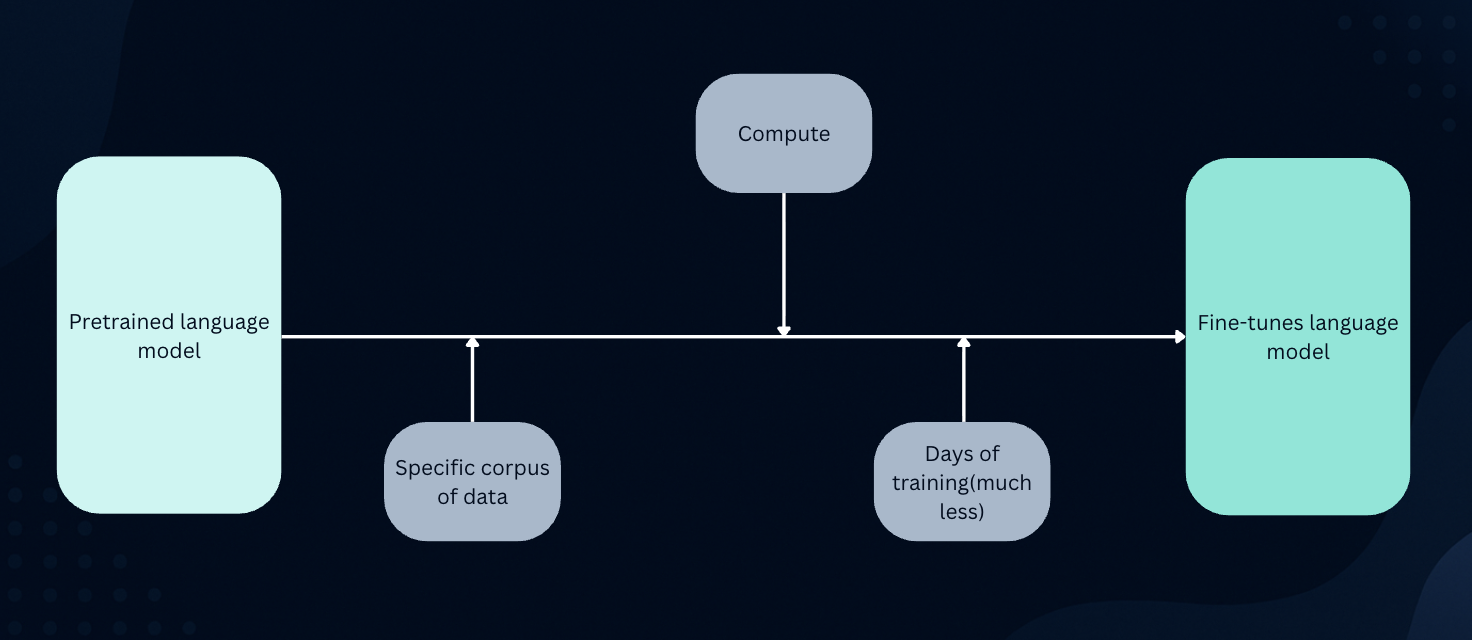

There is one more concept called “Transfer learning” which fine tunes the LLMs coding capabilities. Transfer learning means you start from a model that already knows a lot and adapt it to your target task/domain with much less data and compute than training from scratch. In this case, rather than training a coding model from scratch, a general model’s capabilities are transferred into the coding domain, then specialised for tasks like generation, refactoring, debugging, and test writing.

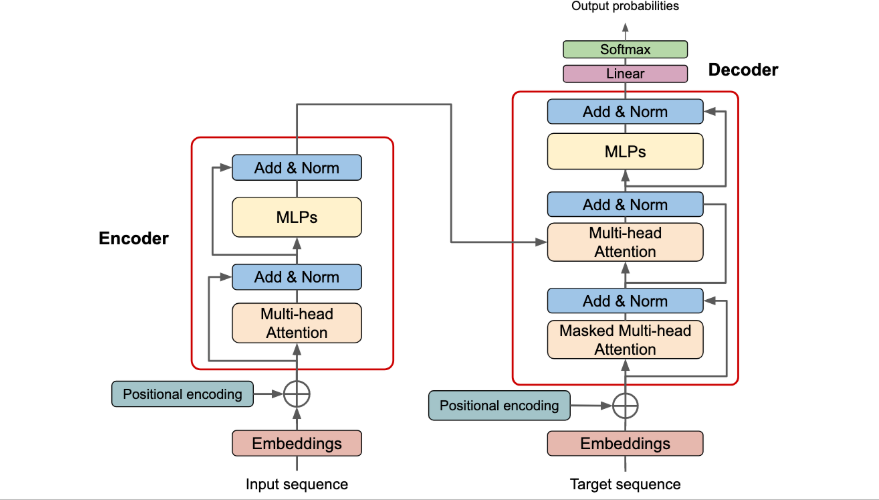

Many modern LLMs, especially those good at code, are based on an architecture called the ‘Transformer’. There are different variants of transformer models in practice. Decoder-only(GPT style) models are used for code completion and the input prompt (e.g., the code you’ve written so far) is fed directly into the Decoder stack. Another variant is encoder-decoder models(T5, BART etc.). These models are less common but are used in specific scenarios, such as code translation (e.g., converting Python to Java). The overall architecture may look complex, indeed it is, but the overall idea and the intuition is not that hard to grasp. Let’s try to uncover a little more.

source: Attention is all you need(https://arxiv.org/abs/1706.03762)

The model can’t read code like a human. First, it has to convert your code into numbers it can process.

Tokenization:

The code is broken down into smaller pieces, or “tokens”. For example:

def calculate_sum(a, b):

may become a list of tokens like:

['def', 'calculate_sum', '(', 'a', ',', 'b', ')', ':']Embeddings:

Each token is then turned into a list of numbers (a vector) called an embedding. This vector captures the token’s semantic meaning, so similar tokens like def and function will have similar numerical representations. The token def might be represented as [0.2, -0.5, 0.7, …]. The token print might be represented as [0.8, 0.1, -0.3, …].

Positional Encoding:

Transformers naturally don’t know the order of tokens. So, a special number is added to each token’s embedding to give it information about its position in the code.

x = 5

y = x + 2This encoding helps the model understand that x in line 1 is being defined, x in line 2 is being used and y comes after x in the code sequence.

This is where the real magic happens. Self attention is where each token pays attention to every other token and weighs their importance. Then a weighted sum of all tokens in the input sequence is calculated, where weights reflect the relevance of each token to the current token.

# Suppose a user types this Python snippet:

def calculate_area(radius):

pi = 3.14159

area = pi * radius *The attention mechanism knows that to predict the next token, it should pay high attention to the variables pi and radius and the * operator, while mostly ignoring less relevant tokens like the def keyword from the line above

Multi-Head Attention:

This is like running multiple attention processes at once. One “head” might focus on variable relationships, another on syntax structure, and another on function scope, giving the model a much deeper understanding of your code.

Masked Multi-Head Attention:

When writing the next token, the decoder pays attention to the tokens it has already written. Masking ensures the model only looks at tokens up to the current point in the sequence. Without the mask, the model would cheat by seeing the answer ahead of time during training. Masking is still used during inference/generation, but it’s not really required because there’s nothing to mask beyond the current step but kept mainly to maintain consistency.

MLPs (Multi-Layer Perceptrons/Feed-Forward Networks)

After attention, each token passes through a neural network that processes the information further. It strengthens useful insights (like recognizing correct syntax patterns) and helps predict the next logical token (like correctly closing brackets or choosing suitable variable names). This is where abstraction happens: the model begins to “understand” high-level patterns, like what an if block does.

Add & Norm (Residual Connections & Layer Normalization)

This layer helps information flow through the network and keep training stable.

if user.is_authenticated:

# more code

return user.profileResidual connections help the model remember that we’re inside an if statement about user.is_authenticated even after processing many lines in between. This helps maintain context through deep processing.

Linear Layer + Softmax

After the final decoder layer, the model produces a score for every possible token in its vocabulary (all known keywords, variables, symbols, etc.). The Softmax function turns these scores into probabilities (like percentages). If the decoder just generated my_variable =, the Softmax output might give a high probability to tokens like 10, “hello”, input(, [, etc., and a very low probability to tokens like def, return, or ). The model typically picks the token with the highest probability as the next one in the sequence.

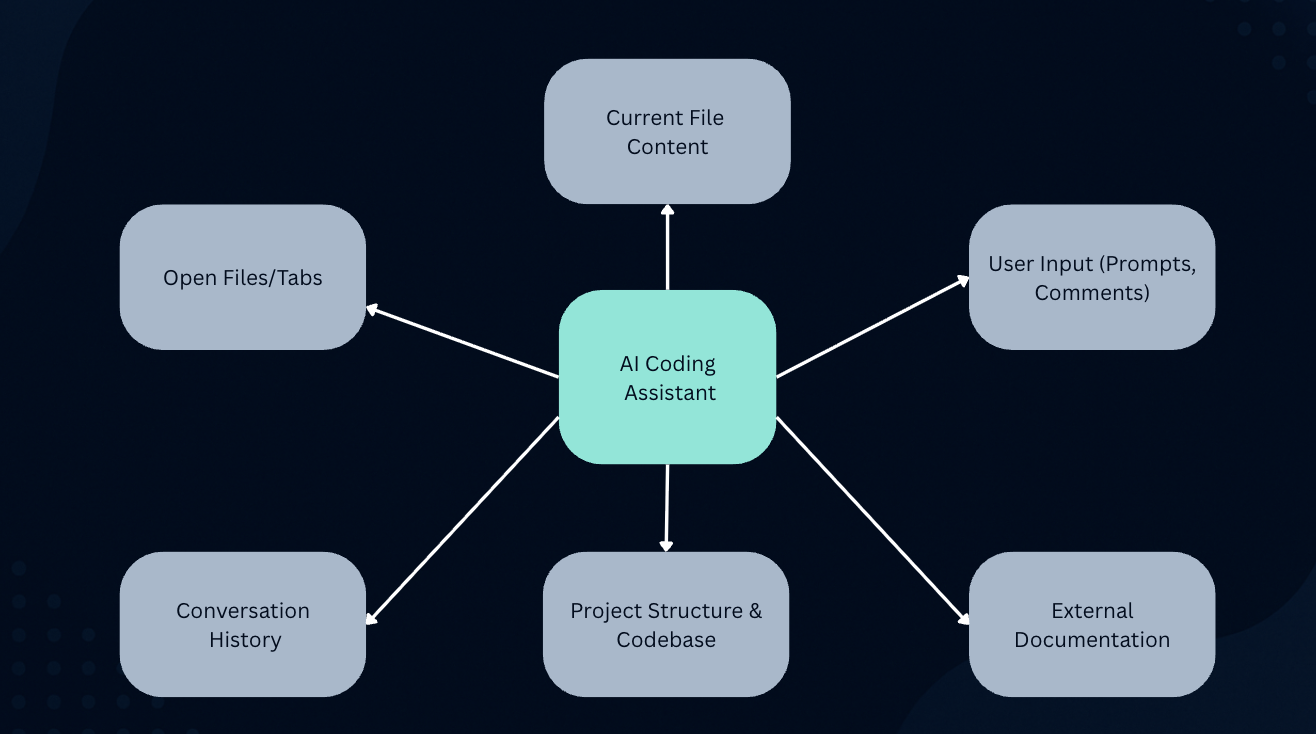

A coding assistant does more than just look at the line you’re currently typing. To provide truly helpful suggestions, it needs to understand the bigger picture. This is what we call context.

AI assistants gather context from many sources:

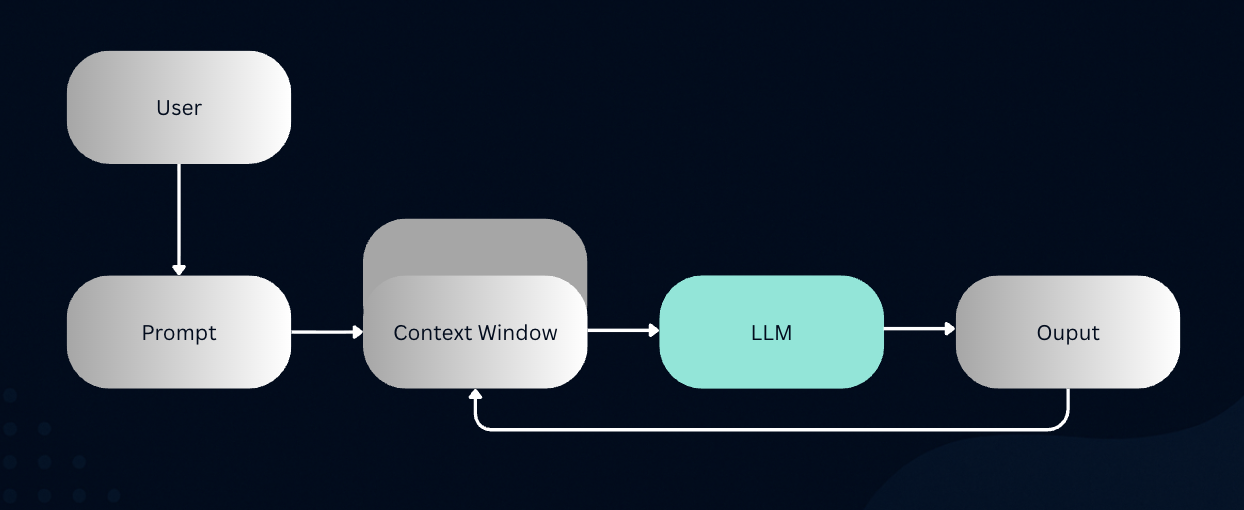

// TODO: Implement error handling, you are giving the AI explicit context.So how does the AI manage all this context? LLMs have a fixed limit on how much text they can consider at once, called a “context window”. You can’t just feed your entire project into the model.

This is where a technique called Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) comes in. It’s a clever two-step process:

RAG is what allows the AI to feel like it knows your entire project without actually processing all of it at once.

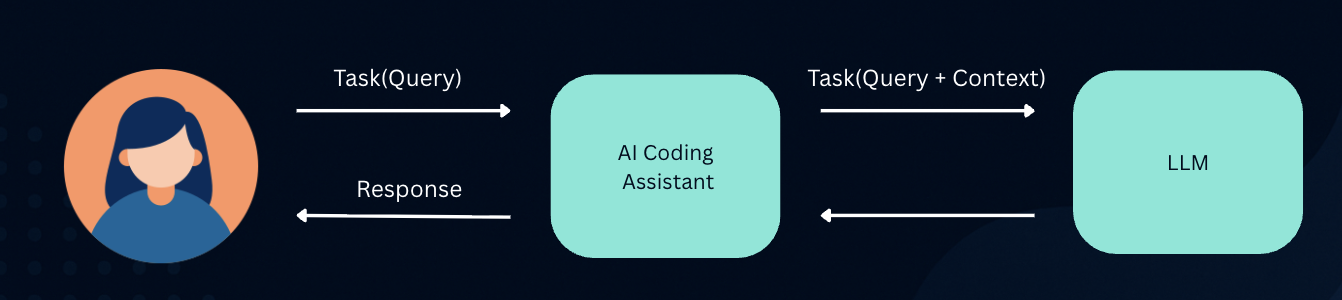

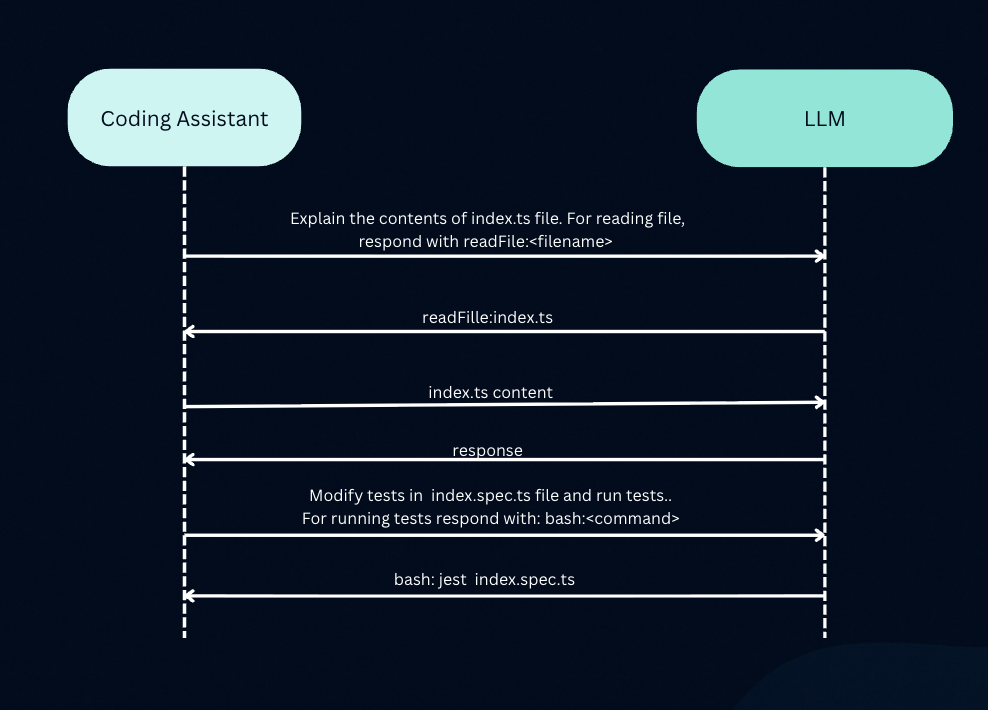

Coding assistants can understand context, but how do they actually do things? Language models, by themselves, live in a text-only world. They can process text and generate text, but they can’t inherently read a file, run a command in your terminal, or check a webpage. So how do assistants solve this? They use a clever system called “tool use.”

When you ask an assistant to do something that requires interacting with your system or external system, it makes use of tools to do the necessary actions. An example listed below:

index.ts file from your computer, and sends its contents back to the LLM.This flow allows the model to effectively “read files,” “write code,” “run commands”, “do web search” , and many other, even though it’s only ever processing and generating text. This advanced skill provides key benefits, such as tackling harder jobs, and enhancing security by not needing to send your entire codebase to an external server for indexing. In fact tools make it possible what is called “agentic mode” in coding assistants.

So, the next time your AI coding assistant finishes your line of code, you’ll know it’s not mind-reading. It’s a sophisticated mix of tokenization, attention ,context, tools etc. all powered by a Large Language Model and a clever RAG system. Happy coding!